We are not talking about far-fetched, rare circumstances either. What career would you like to follow? Name one. Anyone. Politics, and not right and wrong, will decide what happens to you there. And, although it’s easy to say, “I will always do the right thing because I am not afraid of the cost,” as any soldier of God should say, compromise and uncertainty about what the right thing is will always dog you. If you think that your doing of the right thing will actually be recognized for just that, you are in for a rude awakening.

I am only saying this so that you will be spiritually prepared for it when it comes. It’s easy to look back on St. Thomas More’s fight with King Henry as a black-and-white, good-versus-evil situation nearly five-hundred years after the fact, but I bet More faced a great deal of discouragement from those he knew and respected misjudging him and unintentionally blackening his character and intentions. “Who was he to think that he knew better than all the bishops of the realm of England? What a proud man!”

Many of the jobs I have held brought with them degrees of unhealthiness. I have worked for the Church several times, so I am certain this is not just a pagan problem. It’s also a Catholic problem, because most of us are hardly more virtuous than our pagan counterparts. Competition can breed the worst in people. But isn’t competition a healthy means for everyone to better themselves? Ideally, yes. But most people don’t want to compete, don’t feel they can compete, on an equal playing field. So they don’t play by the rules. The first thing they do is appeal to authority. In other words, they tell on you to make themselves appear more worthy of preferment. We are not much above the school yard here, my friends. Did you take too long at lunch (despite a flat tire), speak too loudly, waste paper, play favourites, say something that was offensive, etc. Real or imagined, this is what you will be dealing with in the work force. But what will you do – find a job where people aren’t like this? If they have original sin…

Some environments have been caricatured as political minefields. I have lots of friends who are school teachers – whether it’s the Public or the Catholic Board, schools are sensitive places, where it’s possible to hang yourself a million times a day. Any business with a large number of administrators is dangerous, people whose job it is to listen to and act on such complaints. Universities are the worst. I have learned from insiders that the government is especially bad – it’s very cutthroat, and people who are especially adept, not at being productive, but at manipulating the system, abound. I’ve also been given an inside-look at the world of high-finance. As you are no doubt beginning to realize in the case of Mozilla, politics infects the world of high-finance too, where, if you do not agree with the reigning political philosophy, you will find yourself out of a job. Oh, but the Church is bad too, I have to say again, and I have to tell you this because many of you might be thinking that working for the Church – or various Church-related apostolates – is a great way to live out your Christian vocation. I am not saying it’s not your call to do so. What I am saying, however, is do it for God, and not because what you really want in life is to find a pleasant, enriching environment where everyone is good to each other.

No matter where you are or what you do, people are bad… That’s not a popular thing to say, but take my word for it. I will wait… your experience will confirm what I have said.

The reason why work environments are especially unhealthy today – though I have studied enough history to know that there was never a golden age! – is that today people do not espouse a real idea of the good. People believe in pragmatism, not in virtue. Why? As one of Dostoevsky’s characters said, “If God does not exist… everything is permitted.” Whether they believe He exists or not, people act as if He does not. People do not have a sense of their eternal destiny: that the only thing truly necessary is to be good in the eyes of God. Without God everything is permitted, and everything is done, if people can get away with it.

I’d like to think – and I did when I was younger – that being good pays off in the long run in the world. I used to point to something that once happened to me as proof of this. When I was sixteen or seventeen I worked at a bingo parlor, mostly selling tickets on the floor. Some of the employees stole. They stole tickets; I think they even stole cash. I would not steal. I just wouldn’t. One night I was short $20. It would have been easy enough to steal it and say that it must have fallen out of my pocket. I had a reputation for honesty. Although it looked bad – because stealing was a regular part of life there – I think everyone knew I did not take it. From that I learned that doing the right thing even when people weren’t apparently looking was the best way to protect yourself.

I have since been disavowed of that notion. A few years later I wrote a thesis on Immanuel Kant’s ethical theory for my undergraduate degree in philosophy, specifically, on how the science of ethics depends upon a notion of God. Kant taught that the idea of God is necessary to ethics because that is the only way to justify doing the right thing – the idea that there is a God who will reward you, because, as experience shows, you will not be rewarded in this life for good behaviour. I thought he was wrong about that. I did not think that he was mistaken about God being necessary for ethics, but that he was wrong to think that being good in this world didn’t pay off, as proven by my bingo example. Yet I was wrong, the subsequent twenty years showed me, and Kant was right.

Around that time my Russian History professor, when speaking about Stalin’s purges, said something that has haunted me ever since. He said that in the modern world heroism is meaningless. I am paraphrasing, and twenty years has left a lot to be desired in my clarity, but I think I remember his essential point. What he meant was that when it comes to someone like Stalin, any modern despot, because of the control they can now extend by means of the modern means of communication, the most heroic person can be turned into a heinous villain in the eyes of the world. This was truly offensive to a young, zealous Catholic convert like I was at the time, who dreamt of martyrdom. How would the British have discredited Gandhi, Henry VIII St. Thomas More, the Roman emperors the early Christian martyrs if they had TV, radio and the internet at their disposal, not to mention all their sophisticated eavesdropping methods? And then I come back to the great bishop, Cardinal Mindszenty, and the great Russian author, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, who did survive Stalin and his propaganda machine. They survived with their lives and their reputations more or less intact, although they had certainly suffered a great deal. And yet, compared to these two cases, how many thousands – perhaps millions – are there whose struggles, virtue and heroism we do not know? The 20th Century has been called the century of martyrs, but how many can you name?

I am not saying all of this to discourage you, but to prepare you to take on evil as it really is. You cannot build your house on sand, that is to say, on a false idea of what it is to take on evil and what it costs to fight it. Suffering is not glamorous, said a well-known Catholic blogger recently. She is right. If there is a wrong way to interpret what you do, it will be found. You have to be prepared for this reality. You were not told this as a child, were you?

The motto of my mother’s clan evokes an eternal truth: meane weil, speak weil and doe weil. Live it, but do not be surprised about how your meaning, speech and deeds end up being interpreted. In the movies bad guys are easy to spot with their black hats or their goatees, and good guys their shiny white teeth and manifest good looks. That is just the movies. In real life, the ‘heroes’ of the workplace are probably the most devious. Most of our politicians are morally bankrupt and yet we vote for them time and again. Anyone who can succeed in a world ruled by evil forces is not a person I think you would want to be like. In some places and at certain times, the man of integrity will receive his due. But it will not be long-lived, and his life with be one of suffering and misinterpretation.

One of Job’ so-called friends said to him,

“Surely you know how it has been from of old, ever since mankind was placed on the earth, that the mirth of the wicked is brief, the joy of the godless lasts but a moment.” (Jb 20:4-5)

The implication here was that since Job was suffering, he must have done some hidden evil. For, this ‘friend’ goes on to say,

“Though evil is sweet in his mouth and he hides it under his tongue, though he cannot bear to let it go and lets it linger in his mouth, yet his food will turn sour in his stomach; it will become the venom of serpents within him. He will spit out the riches he swallowed; God will make his stomach vomit them up.” (Jb 20:12-15)

In other words, everything will become very clear in the eyes of all who did what and why. And yet Christ had this to say,

Now there were some present at that time who told Jesus about the Galileans whose blood Pilate had mixed with their sacrifices. Jesus answered, “Do you think that these Galileans were worse sinners than all the other Galileans because they suffered this way? I tell you, no! But unless you repent, you too will all perish. Or those eighteen who died when the tower in Siloam fell on them—do you think they were more guilty than all the others living in Jerusalem?” (Lk 13:1-4)

But that is exactly how the world thinks.

Worst of all, of course, is the fate of someone who broadcasts his Christian convictions publicly. Bear this in mind, though: you will not be left alone whether you live your Christian faith publicly or not. So, if you are going to suffer, you might as well suffer for doing good, as St. Peter says, “It is better, if it is God’s will, to suffer for doing good than for doing evil.” (1 Pt 3:17)

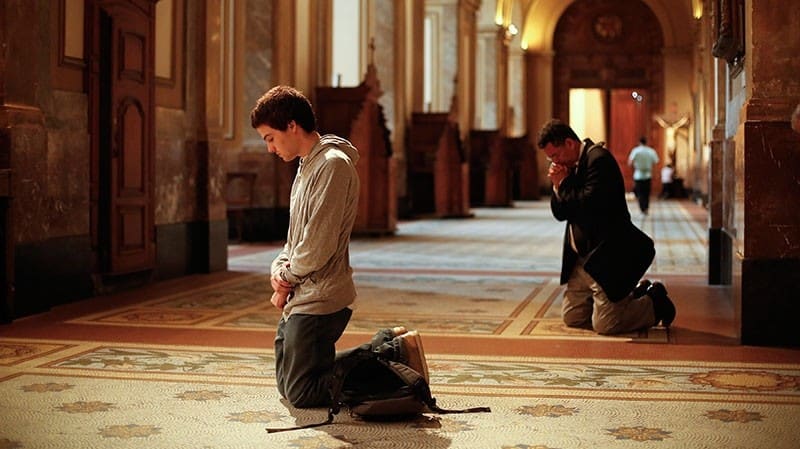

When he was a young man, St. Benedict was so disgusted by how people lived that he went to the wilderness to live as a hermit. The thought of doing just that has occurred to me more than once. It might be your call to do so, but what I know for a fact is that you must erect a sort of hermitage in your heart wherever you are.

Colin wrote this Article for the Knights of the Holy Eucharist. He has been married to Anne-Marie since 1999, and they are proud to raise their six children, in a small town in Ontario, Canada. Colin has a PhD in Theology and works tirelessly to promote the Gospel. “Just share the Word,” is what he believes the Lord says to him – and so he does. He recently founded The Catholic Review of Books, a printed journal and website dedicated to “all things books” from the perspectives of faithful Catholics. He is fascinated by the concept of chivalry as it applies to being a man and a father in today’s crazy world.